On December 24th, as most of the nation prepared for the traditional week of rest of and relaxation between christmas and new years, something extraordinary happened to the Australian environmental movement. In one 24 hour period, this country lost three of its great protectors – Bill Ryan, John Flynn and Lyle Davis each passing.

.

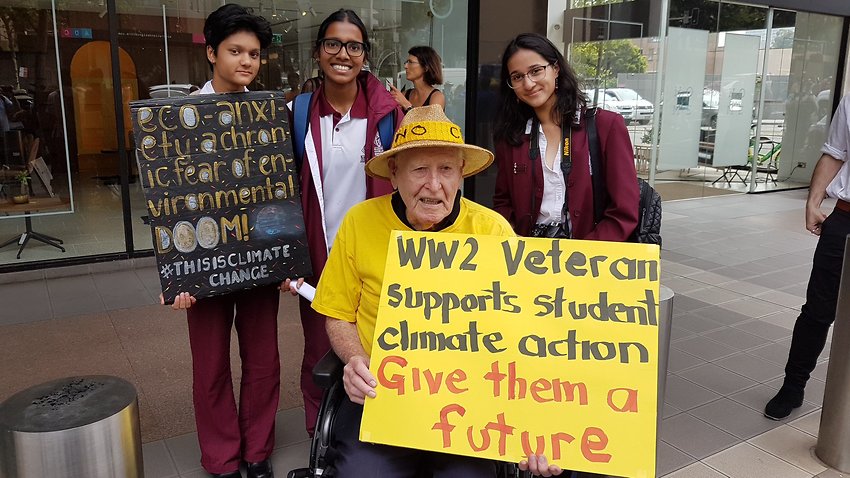

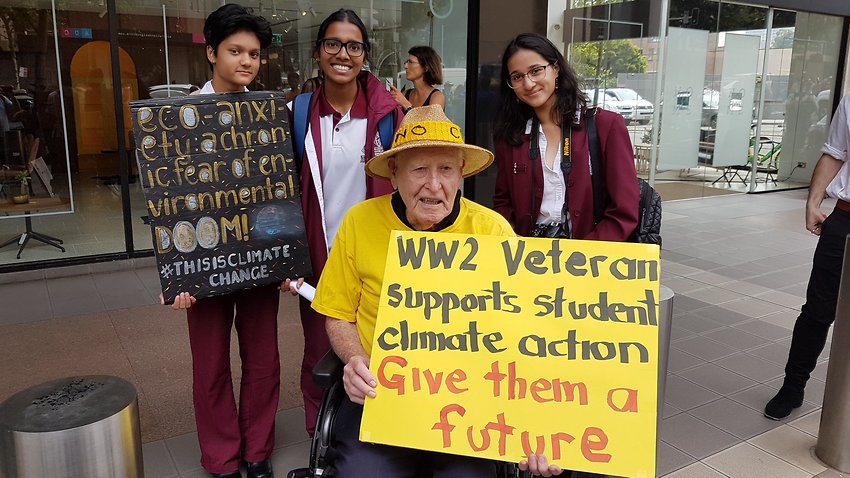

Bill Ryan was 97 years old. He lived a long and full life. Bill told me he rarely saw his father as a child because the ardent communist was off preaching revolution to unemployed workers during the great depression. In World War II, Bill was a soldier. He copped a bullet in his back at Kokoda in the war against the spread of fascism. But in his later years he dedicated his life to the non-violent fight against a different kind of global threat. Bill became an environmental activist in his late 80’s, and was arrested seven times in protests against the fossil fuel industry.

Bill was a regular fixture at climate protests in recent years. He did a weekly vigil with signs and pamphlets in Martin Place for a long time; but also ventured out to direct action protests, blockade camps, late night stealth missions. His quiet, dignified presence was always valued in spaces often full of the loud, frantic energy of youth.

In 2017, SBS interviewed Bill at a protest. “The younger generation are here in strength and I can pass on with a smile on my face” he said. “But until that’s happens I’ll fight on.”

.

John Flynn shared his name with a famous Australian doctor, but it was the health of Australia’s old growth forests that was the great concern of a man universally known as “Flynny”.

Details like exactly when Flynny began protesting seem irrelevant. Like the ancient trees he was so dedicated to preserving, he just seemed to belong in that East Gippsland forest – rooted in the soil, deriving his sustenance from the ecosystem around him.

No obituary will attempt to count the number of times Flynny was arrested. He lived for the forest, and taking direct action to protect it came naturally to him. “Lock on or fuck off” was a catchphrase of his, capturing – for better or worse – his overwhelming passion for the cause. And while charismatic people skills are not what he is likely to be remembered for, Flynny was a much-loved figure who inspired many and probably even won a few grudging admirers among the timber industry and government for whom he was a perpetual thorn in the side.

Flynny contracted cancer this year and underwent chemotherapy and radiation treatment. Complications from the treatment led him back into hospital where he was placed in an induced coma. Over the years he lived to see much of the forest he fought for protected, and this year it was announced that Victoria would be phasing out native timber logging – a victory probably impossible without Flynny’s tireless work. The terms of it though would not have satisfied him, and he would have kept fighting for that forest until the very end.

.

Lyle Davis was a Yuin man, his country the south coast of New South Wales. Like most aboriginal people, he grew up with first-hand experience of the injustice of the world, and went to his first protest in the early 70’s to bring the troops home from Vietnam. As a young man, Lyle worked as a hairdresser; and he never lost that eye for style. In his later years he cut a distinctive figure at protest events with his long beard, Akubra and leather boots.

He was also a distinctive figure because he lost one arm in a car accident. He was a tough and resourceful man though, who could do most things one handed and would joke about whatever he couldn’t. For long stints of his last decade he lived at protest camps around the country, tirelessly volunteering what help he could and taking on somewhat of a morale leadership role – for many young activists around the country he was Uncle Lyle.

Lyle was a proud Yuin and aboriginal man, but the other tribe he belonged to and loved was the activists. He had endless love for those who dedicated themselves to improving this world, a fact he happily and frequently reminded them. “You’re mad, deadly, beautiful people!” he would exclaim repeatedly to the occupants of Camp Binbee, the Adani blockade camp where Lyle lived for half of 2019.

He lived a hard life, and struggled at times with addiction. No stranger to pain, towards the end of this year he mentioned pain in his mouth. At the doctor’s he was diagnosed with advanced cancer. This was one struggle that was going to be difficult to fight. Eventually Lyle went back to Sydney to be closer to his home and family, but not before a beautiful ceremony at Camp Binbee to commemorate the frontier wars. That struggle to protect country was one that never ended for Lyle.

.

The charred landscape seems to mourn the passing of the three eco-warriors. Coming amidst the broader grief of a nation grappling with the disastrous consequences of climate change, the day of loss was a shock that made this Christmas not so merry for the Australian environmental movement. But it need not be an entirely somber occasion, as these were three people who took seriously the idea of legacy – the question of what consequences we leave behind of our existence on earth.

Much has been written about the negative effects humans and our lifestyles can have on the natural environment, but the lives of Bill Ryan, John Flynn and Lyle Davis are a reminder that this doesn’t have to be our only footprint. They were people who dedicated their lives to a greater cause – to speaking up for justice and for our earth. Their struggle is over now, but the world is better off for it. Their bodies are no longer here, but their legacy lives on.

Recent Comments